p. 82 desde "Post Street was empty" até "the small ovals of bread he had sliced"

O excerto em análise pertence ao capítulo 9 da obra de Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon, em que se adensa a intriga romântica/melodramática entre o detective Sam Spade e a sua cliente, apresentada ora como vítima ora como potencial criminosa traiçoeira, Brigid O’Shaughnessy. O título do capítulo coincide com o nome próprio desta, “Brigid”, e o excerto em análise mostra-nos como ela contracena com Sam Spade, realçando certos tropos de género neste policial.

O excerto inicia-se na rua, passando depois para o interior doméstico da casa de Sam Spade, onde este e Brigid representam os gestos de um casal preparando uma refeição. Sabemos, pelo ocorrido antes, que é de noite, o que justifica o estado deserto das ruas percorridas por Sam no encalce de alguém que o vigia – uma situação que nos recorda o ambiente de paranoia criado pelo precursor do género policial Edgar Allan Poe, em “The Man of the Crowd” – porém, aqui a cidade está deserta, reflexo da hora tardia e também do medo das ruas sombrias de São Francisco, onde se desenrola a ação

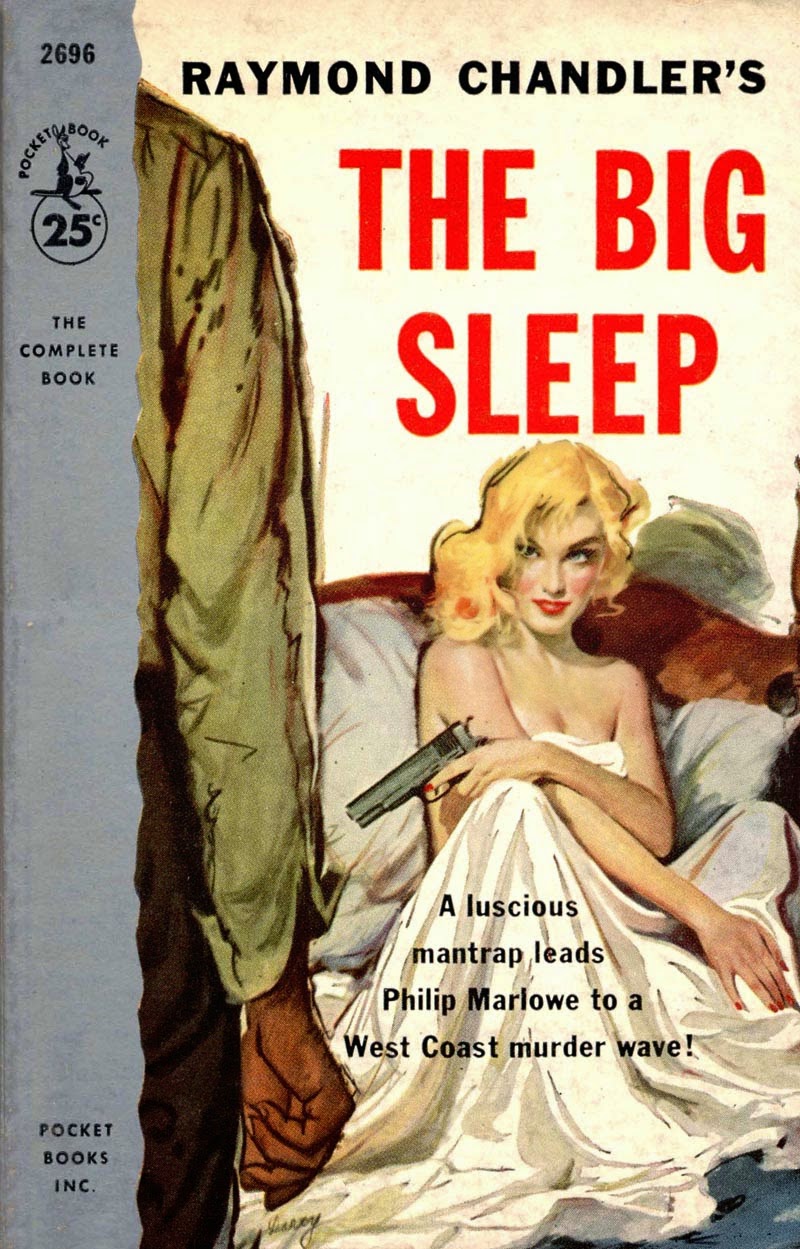

A descrição dos movimentos de Spade no bairro noturno testa o estilo realista, frugal e seco, que Raymond Chandler atribui a Hammett no ensaio “The Simple Art of Murder.” Temos uma indicação rigorosa dos movimentos do detective na rua, através de verbos de ação seguidos de deíticos de lugar – advérbios relativos aos pontos cardeais: “walked east”, “crossed”, “walked west”, “recrossed”.

O regresso ao espaço doméstico dá-se através de uma interessante palavra de transição “passageway”, um símbolo do limiar que também serve para introduzir de forma ambivalente e algo tortuosa Brigd O’Shaughnessy, “standing at the bend”. Para mais, na posse de pistolas que pertenciam a um homem (Cairo), a personagem parece assumir o controlo fálico, sendo o erotismo disso reforçado um pouco mais à frente com a frase: “The fingers of her left hand idly caressed the body and barrel of the pistol her right hand still held.”

As palavras de Sam Spade, em discurso direto, demonstram algo que pela narração sabemos ser mentira. Há, portanto, uma dissociação entre a narrativa (o que se conta), e a ação (o que se mostra), sendo que este contraste entre as categorias enunciadas por Waine Booth como “tell” e “show” é característico de romances em que está em causa o engano e a ilusão.

Segue-se uma progressão das duas personagens pelo interior da casa, desde o mais público, a entrada, passando pela sala de estar e até à cozinha, anunciando também o adensar da intimidade entre o casal. Neste percurso, Brigid será mais uma vez colocada no limiar – “came to the door”, “doorway”.

É interessante que seja Brigid a pôr a mesa enquanto o detective cozinha, já que isso indica uma relativa inversão dos tradicionais papeis de género nos trabalhos domésticos, com a mulher a cozinhar e o homem a “ajudar”. Por outro lado, Spade é retratado no controlo do seu espaço (é a sua casa) e há algo na insistência no verbo “slice” aplicado às fatias de pão preparadas que remete de novo para a precisão do seu modus operandi. Além disso, o excerto revela o detective como um calculista, preparado para qualquer situação, sendo que por outro lado Brigid parece dona da sua sexualidade e disposta a usá-la para obter poder, como acontecerá no fim do capítulo.